By Guest Contributor Eccentric Yoruba, cross-posted from Beyond Victoriana

Dandyism and the Black Man

A dandy is a man who places extreme importance on physical appearance and refined language. It is very possible that dandies have existed for as long as time itself. According to Charles Baudelaire, 19th century French poet and dandy himself, a dandy can also be described as someone who elevates aesthetics to a religion.

In the late 18th and early 19th century Britain, being a dandy was not only about looking good but also about men from the middle class being self-made and striving to emulate an aristocratic lifestyle. The Scarlet Pimpernel is one of literature’s greatest dandies; famous historical dandies include Oscar Wilde and Lord Byron.

These days the practice of dandyism also includes a nostalgic longing for ideals such as that of the perfect gentleman. The dandy almost always required an audience and was admired for his style and impeccable manners by the general public.

The special relationship between black men and dandyism arose with slavery in Europe particularly during England’s Enlightenment period. In early 18th century, masters who wanted their slaves to reflect their social stature imposed dandified costumes on black servants, effectively turning them into ‘luxury slaves’. As black slaves gained more liberty, they took control of the image by customising their dandy uniforms and thereby creating a unique style. They transformed from black men in dandy clothing to dandies who were black.

The special relationship between black men and dandyism arose with slavery in Europe particularly during England’s Enlightenment period. In early 18th century, masters who wanted their slaves to reflect their social stature imposed dandified costumes on black servants, effectively turning them into ‘luxury slaves’. As black slaves gained more liberty, they took control of the image by customising their dandy uniforms and thereby creating a unique style. They transformed from black men in dandy clothing to dandies who were black.

This style also served to differentiate black dandies from other dandies, most notably, the Macaroni dandies whose fabulous style of dress was thought of as obscene.

One of the pioneers of black dandies in England was Julius Soubise, a fencing master, poet and actor who was once owned by the Duchess of Queensbury. Julius Soubise would appear at London’s high society venues wearing “red-heeled diamond-buckled shoes and buttock-skimming breeches”.

One of the pioneers of black dandies in England was Julius Soubise, a fencing master, poet and actor who was once owned by the Duchess of Queensbury. Julius Soubise would appear at London’s high society venues wearing “red-heeled diamond-buckled shoes and buttock-skimming breeches”.

This type of style evolved and hopped continents from London to Harlem, which during its famous Jazz Age adopted the zoot suit. The zoot suit marked the evolution of black dandyism in the 1930s. The “zoot” from the zoot suit came from the term in jazz culture that described anything performed in an extravagant fashion. Jazz musicians such as Duke Ellington, Louis Jordan and Cab Calloway sported zoot suits and the suit itself became central to any dandy’s wardrobe.

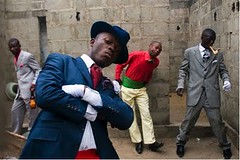

Though today the most famous black dandies are Americans like Andre 3000, black dandyism can also be found in other parts of the world. In particular, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, there currently exists a subculture of elegant gentlemen who spend their last dime on looking good and live under strict moral codes.

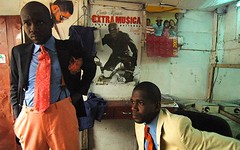

Those of us who grew up listening to and watching music videos from the DRC are quite used to seeing the expensive-looking and multi-coloured suits worn by Congolese musicians such as Koffi Olomide. Yet most of us did not know about the entire subculture that revolves around looking exquisite. May I present La Société des Ambianceurs et Persons Élégants or in English: the Society for the Advancement of People of Elegance.

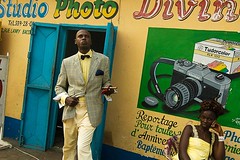

As that is a mouthful so it is just SAPE. “Sape” comes from a French slang that means “dressing with class” and the term Sapeur is an African word that refers to someone that is dressed with great elegance. The Sapeurs as the name suggests are elegant and stylish men from Congo who roam the streets of Brazzaville and Bacongo in Western suits and usually with cigars, and the occasional pipe, between their lips. These are men who are so obsessed with looking good and designer clothes that they sometimes place more importance on clothes than anything else.

As that is a mouthful so it is just SAPE. “Sape” comes from a French slang that means “dressing with class” and the term Sapeur is an African word that refers to someone that is dressed with great elegance. The Sapeurs as the name suggests are elegant and stylish men from Congo who roam the streets of Brazzaville and Bacongo in Western suits and usually with cigars, and the occasional pipe, between their lips. These are men who are so obsessed with looking good and designer clothes that they sometimes place more importance on clothes than anything else.

A look at the history of the SAPE

The first Grand Sapeur was G.A. Matsoua, who in 1922 was the first Congolese to return from Paris dressed entirely in French clothes. While it is not entirely clear where exactly the SAPE movement started from, it appears to have been heavily promoted by Papa Wemba, a pioneer soukous (African rumba) musician who in the 1970s began upholding the Sapeur culture as a set of moral codes with heavy emphasis on high standards of personal cleanliness, hygiene and smart dress among Congolese youths regardless of societal differences.

This moral code, however, also had a political motive. Papa Wemba initially introduced the culture as a challenge to the strict dress codes that were imposed by the government at that time who effectively outlawed Western styles of dress. In 1974 after the DRC had recently come out of colonisation and had gained its independence from France, the government lead by Mobutu Sese Seko banned all European and Western styles of imported clothing in favour of a return to traditional African clothing. Papa Wemba challenged these strict dress codes by insisting that it should be a pleasure rather than a crime to wear clothes from Paris and by setting an example for impressionable young men by dressing outlandishly. At this time, the culture also was heavily associated with music, since Papa Wemba supported young talented musicians such as Koffi Olomide.

This moral code, however, also had a political motive. Papa Wemba initially introduced the culture as a challenge to the strict dress codes that were imposed by the government at that time who effectively outlawed Western styles of dress. In 1974 after the DRC had recently come out of colonisation and had gained its independence from France, the government lead by Mobutu Sese Seko banned all European and Western styles of imported clothing in favour of a return to traditional African clothing. Papa Wemba challenged these strict dress codes by insisting that it should be a pleasure rather than a crime to wear clothes from Paris and by setting an example for impressionable young men by dressing outlandishly. At this time, the culture also was heavily associated with music, since Papa Wemba supported young talented musicians such as Koffi Olomide.

Sapeurs held European haute couture as a religion which was practised in absolute serious. There were special Sapeur dances held and even manifestos and codes to govern the lives of Sapeurs. Some of these codes include 10 ways of walking in order to show off clothes to the best degree, and the strict three colour code where the maximum number of colours that can be worn should be three.

At the height of his success, Papa Wemba had established a “village” comprising his family home and the surrounding streets in which the strict Sapeur code was enforced. Youths and musicians visited this village to acquire cool points while Papa Wemba reigned as “chief”. All other sorts of positions exist among the Sapeurs such as “high priest of cloth” and “chancellor of designer labels” positions which are based on personal flamboyance and the size of expensive wardrobes.

At the height of his success, Papa Wemba had established a “village” comprising his family home and the surrounding streets in which the strict Sapeur code was enforced. Youths and musicians visited this village to acquire cool points while Papa Wemba reigned as “chief”. All other sorts of positions exist among the Sapeurs such as “high priest of cloth” and “chancellor of designer labels” positions which are based on personal flamboyance and the size of expensive wardrobes.

In typical dandy fashion, the Sapeurs consider themselves artists and are respected and admired in their communities. Sapeurs are typically invited to events such as weddings to add a touch of elegance to special occasions. Yet quite uncharacteristic is the Sapeur’s code of conduct, being a Sapeur is not only about dressing and looking amazing, it is also about impeccable manners. It is about style, it is about gestures that differentiate one Sapeur from others.

For example, the cigar which is the ultimate symbol for the Sapeur is considered to give added value to the outfit. While some Sapeurs never smoke their cigars, those who do are required to ask their neighbours if it is okay for them to light their cigars even though they may not be in a non-smoking area.

For example, the cigar which is the ultimate symbol for the Sapeur is considered to give added value to the outfit. While some Sapeurs never smoke their cigars, those who do are required to ask their neighbours if it is okay for them to light their cigars even though they may not be in a non-smoking area.

The dark side to this movement is the lengths some Sapeurs go and have gone through to get their expensive designer clothes. Some have resorted to illegal means to obtain their suits while others have spent time in jail. The infamous Papa Wemba also spent jail time for bringing people into Europe illegally to buy clothes by having them pose as his band members.

While reading about Sapeurs elsewhere online, a lot of emphasis seems to be placed on the fact that most of the men who are part of this subculture come from very impoverished communities. There is lot of talk on just how far these men go in order to buy an expensive suit and how the SAPE is a form of escapism for “poor downtrodden African youths”. The discrepancy between the elegance and style that make a Sapeur and the poor conditions of living are shown as a clash of worlds.

While reading about Sapeurs elsewhere online, a lot of emphasis seems to be placed on the fact that most of the men who are part of this subculture come from very impoverished communities. There is lot of talk on just how far these men go in order to buy an expensive suit and how the SAPE is a form of escapism for “poor downtrodden African youths”. The discrepancy between the elegance and style that make a Sapeur and the poor conditions of living are shown as a clash of worlds.

This sort of thinking rubs me the wrong way. I personally believe the Sapeurs are awesome and this is not limited to the steampunk vibe I got from looking at images of Sapeurs. However, whether you believe the Sapeurs are nothing but extremely materialistic young men or you accept that they are artists who strive to crave their identity through fashion, I think we can all agree that they do so while looking great.

For more information, click on any of the linked images above. Also, check out this great photo essay, The Congolese Sape by Hector Mediavilla.

For more information, click on any of the linked images above. Also, check out this great photo essay, The Congolese Sape by Hector Mediavilla.

Posted via email from the Un-Official Southwestern PA Re-Entry Coalition Blog